Investment Risk as Price Volatility

In finance, a common interpretation of risk is price volatility, which is defined as the magnitude of price fluctuation. In other words, the more volatile an asset's price, the more risky it is. This notion, although frequently taught in business and finance schools, is severely limited in its ability to accurately describe risk and is often incorrectly applied. In fact, many great investors like Warren Buffet and Seth Klarman consider the idea of using volatility as a measure of risk as preposterous. The logic is that historical price information (in the form of realised volatility) does not capture the underlying fundamentals of the asset, especially when trying to forecast potential price appreciation or the probability of permanent loss of invested capital. Nevertheless, there is some utility in the idea which will explored in the following discussion.

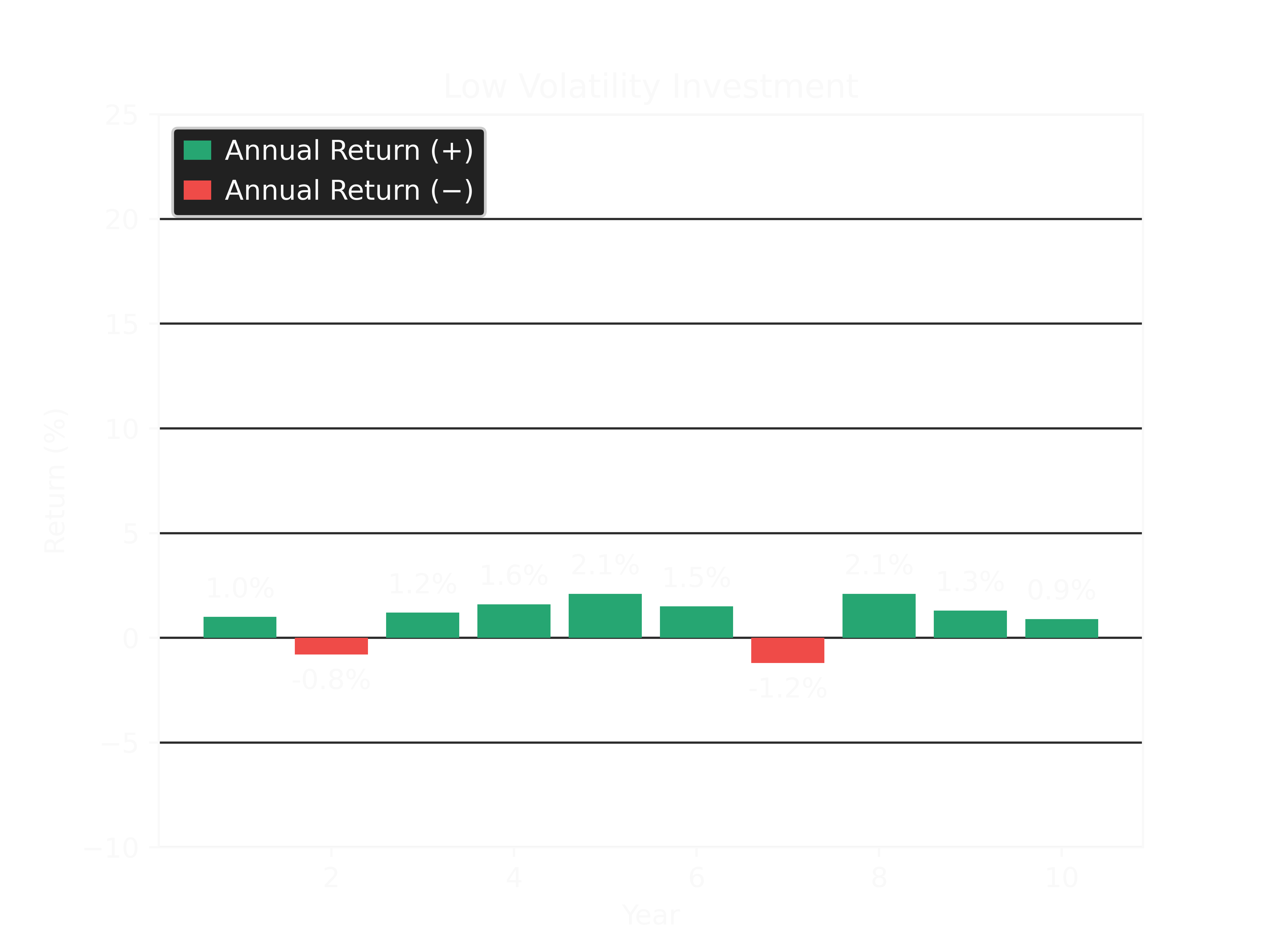

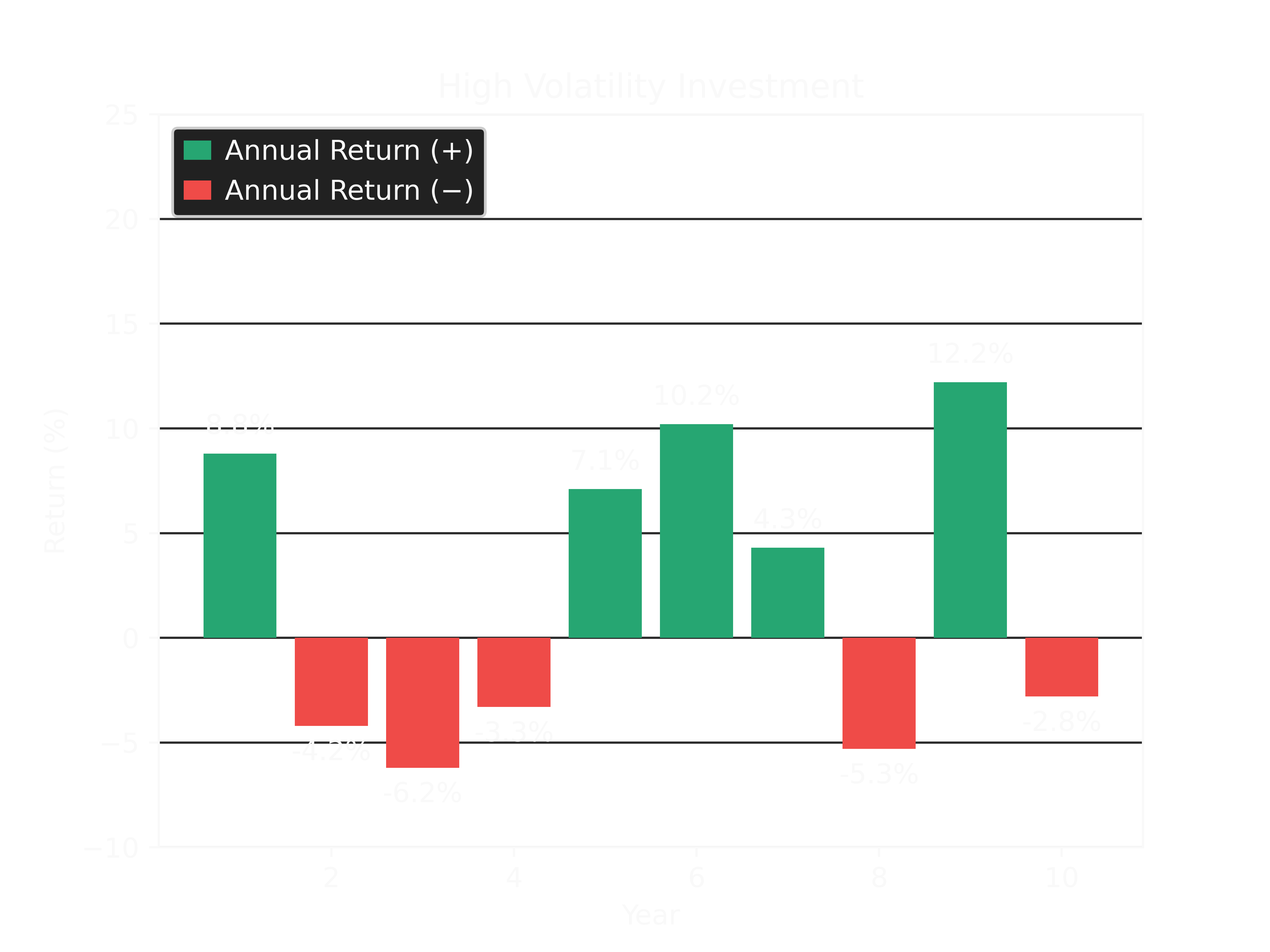

Consider the following examples of low and high volatility investments over ten (10) years.

One can see that the low volatility investment has comparatively smaller and less frequent losses than the high volatility counterpart.

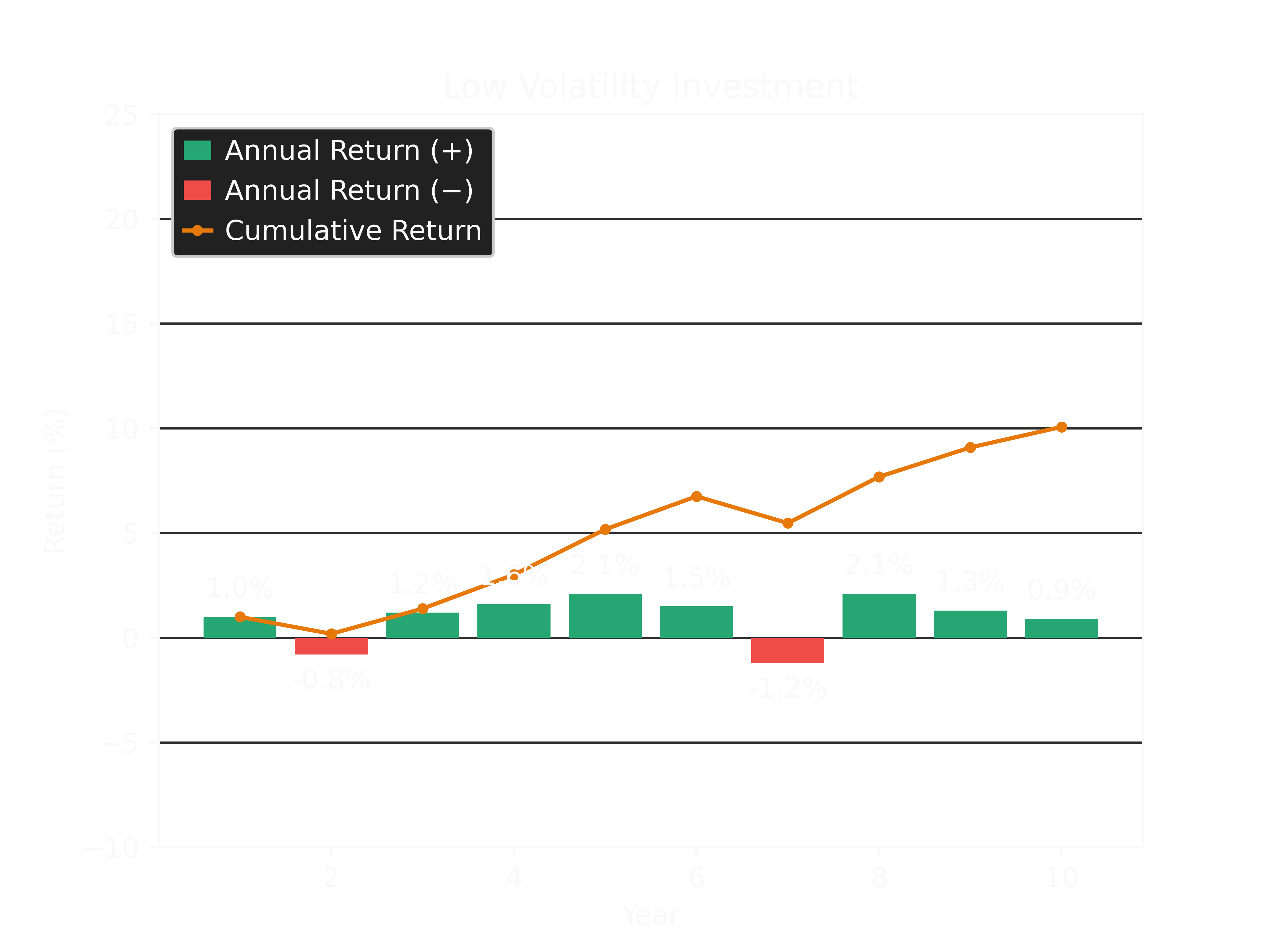

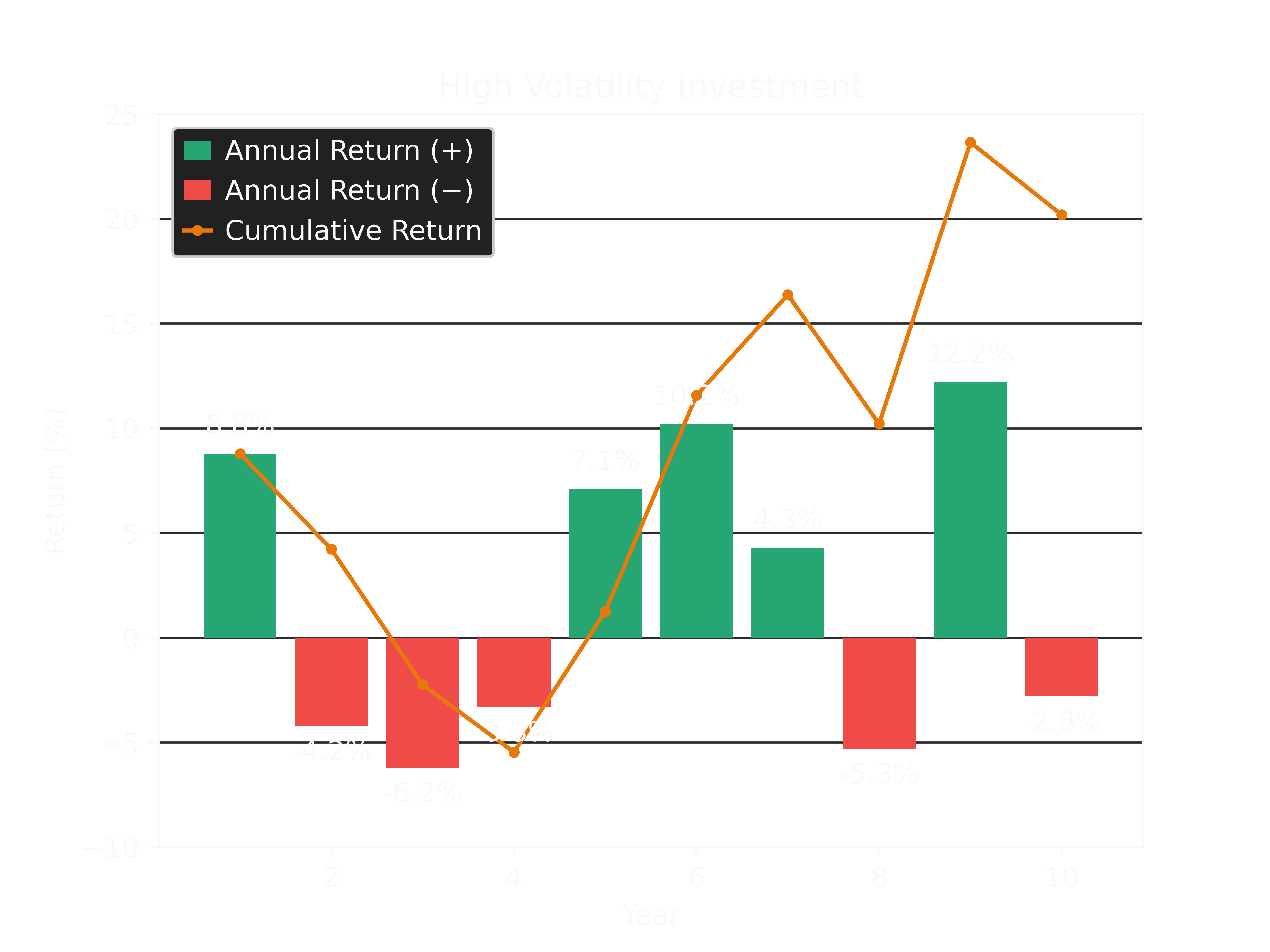

For some people or entities, interpreting risk as this concept of price volatility makes sense. For example, certain institutions, companies or even individuals may have a requirement to maintain specific asset valuations on their balance sheets for contractual or business reasons. Alternatively, an investor may have a short-term investment horizon, after which they must deploy the funds from the portfolio at a value greater than or equal to the original amount invested. High volatility portfolios, by definition, do not suit either of these objectives. To help visualise why this is the case, one can plot the cumulative returns of both investments.

From the graphs, it can be seen that the cumulative return of the low volatility investment steadily increases over time, and does not dip into negative territory. Such a portfolio would be ideal for those looking to maintain steady asset valuations and/or only invest for a short period as mentioned previously. In contrast, the cumulative return of the high volatility investment fluctuates significantly and even goes negative for a portion of the holding period. For obvious reasons, this does not suit the objective of maintaining steady asset valuations, nor does it work for those with short-term investment horizons and a requirement to deploy the funds invested elsewhere at or above initial value. For example, using the high volatility returns shown, if an investor had to exit their investment after the fourth year, they would have lost -5.46%. Whereas, the low volatility option would have resulted in a gain of +3.02%. However, over the full ten (10) years, the low volatility investment only returned a cumulative gain of +10.07%, while the high volatility investment returned +20.20% (approximately double the returns).

This example illustrates the effect the investment holding period has on returns. Specially, that the longer the holding period, the lower the probability of loss and therefore the higher probability of gains.

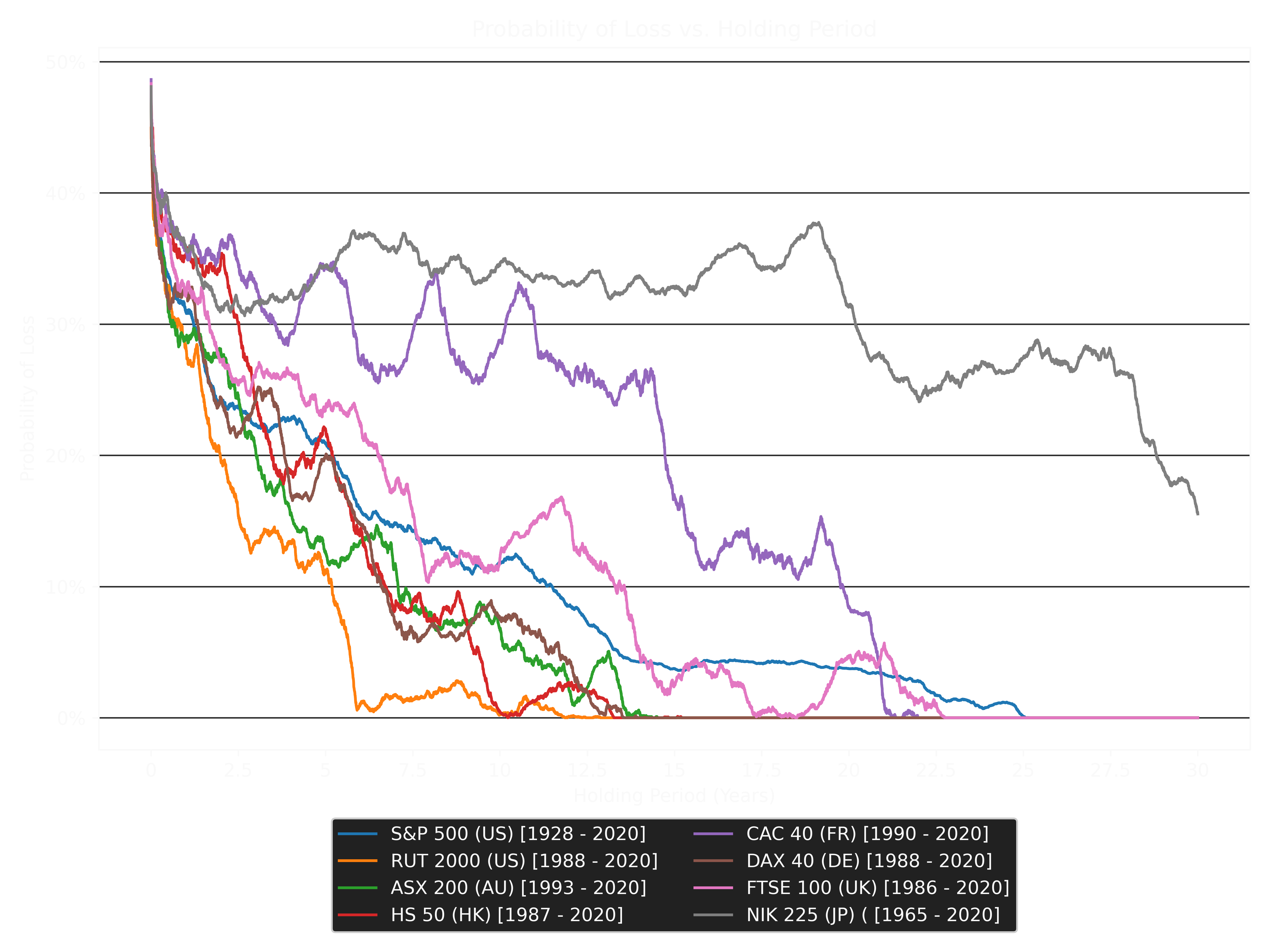

To better showcase this phenomenon, the pricing data of various stock indices were used to calculate the probability of loss over different holding periods ranging from one (1) day to thirty (30) years: where each holding period acted as window that was then passed over the available data. One can see that the affect of stock market volatility over longer holding periods is less pronounced than the shorter counterparts.

While for some people and entities this interpretation of risk as price volatility may make sense, for others, it is a poor interpretation that doesn't fully capture the essence of the original definition: that risk the probability of undesirable outcomes, or more specifically for investors, the probability of permanent loss of capital.